Tan Mu: Signal

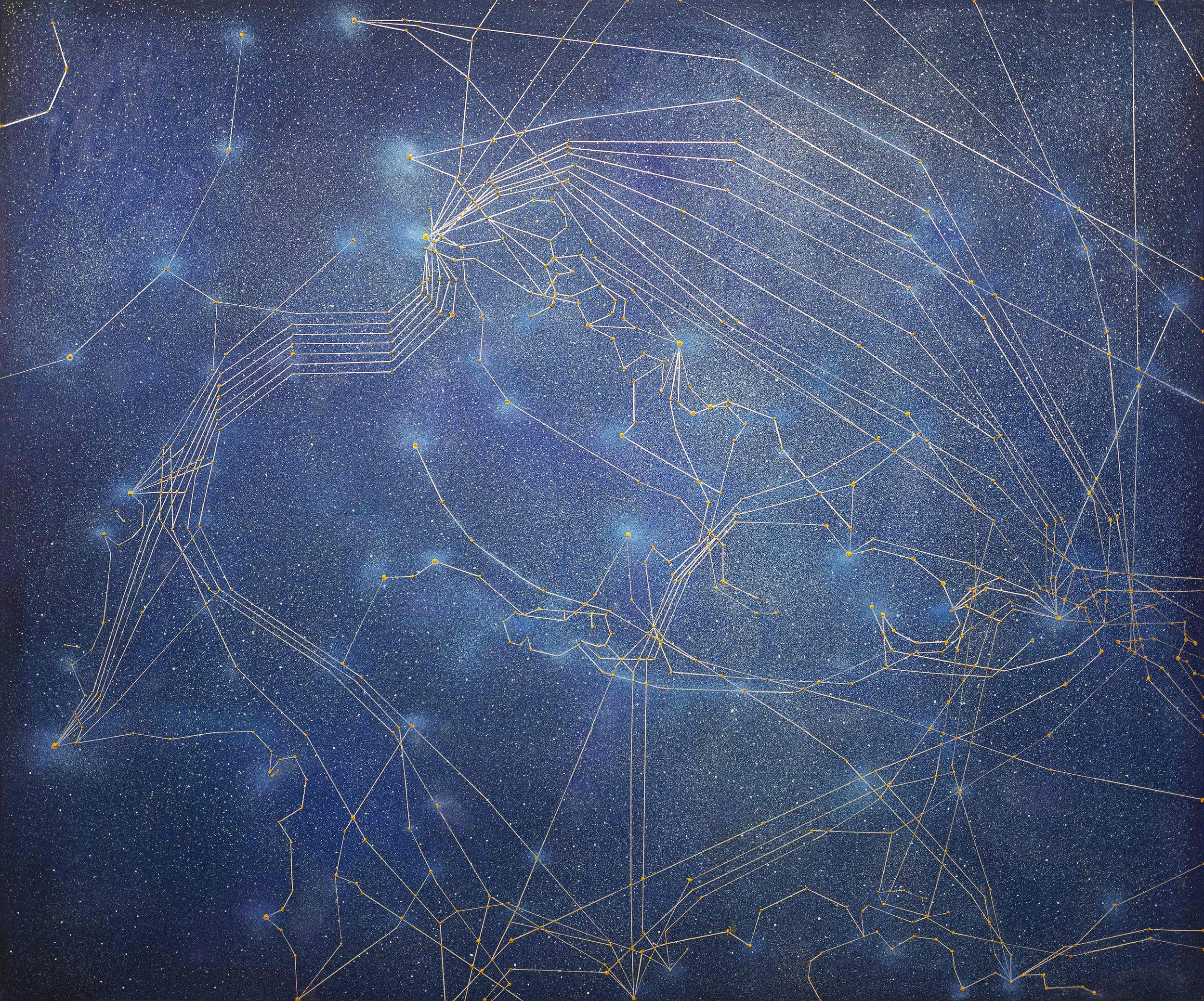

Tan Mu’s ongoing Signal series is a sustained artistic investigation into the invisible architectures of global communication. Grounded in infrastructure, media geography, technological poetics, and human perception, the series transforms submarine fiber-optic networks into symbolic “digital constellations”—bridging abstraction and representation, emotion and system. Mu reimagines these hidden infrastructures not merely as technical constructs but as vessels of collective memory and human connection. By fusing planetary systems with individual and cultural histories, Signal creates poetic diagrams of connection and rupture, mapping time, scale, and collective presence.

BEK hosts the programming around Tan Mu’s Signal series, drawing on the artist’s longtime dedication to identifying, documenting, and interpreting historic moments in science and technology. The programs respond to Signal’s visual and conceptual complexity in situating one’s being in the world on a cosmic scale and aim to build a network of artists and scholars for collaborative multimedia and cross-disciplinary works and events.

As part of a longterm collaboration between Tan Mu and BEK Forum on Signal, the exhibition features five paintings from the series, which depict the undersea telecommunication cables that connect and compose our global, techno-human society. This body of work, grounded in Tan Mu’s oil painting technique and diving experience, creates original, milestone imagery that reflects our evolving relationship with both technology and one another.

Having entered top international collections since its debut at Art Basel Miami Beach 2024, the Signal series will have its first comprehensive solo exhibition this Fall at BEK Forum, accompanied by artist talks, music performance, and an artist book.

Tan Mu (b. 1991, Shandong, China; lives and works in the United States) is a contemporary artist whose practice investigates the hidden infrastructures of technology, data, and signal shaping contemporary life. Working primarily through painting and visual systems, her work investigates how global structures intersect with human perception and collective memory.

Combining traditional oil painting with expanded visual tools such as microscopes, satellite imagery, and scientific visualization, Tan Mu operates at the intersection of technological history and embodied experience. She approaches technology as both an extension of the body and an externalized form of memory, developing compositions that interweave biological, computational, and cosmic structures—from embryos and neurons to logic circuits, quantum computers, data nodes, and celestial bodies. Through this layered visual language, her work translates abstract systems into lived experience, bridging the visible and the invisible.

Her practice is structured through an atlas, a methodological system that links research, archival material, and painting. The atlas serves as a comparative and diagrammatic framework for analyzing heterogeneous information environments, including submarine cables, glaciological imaging, cellular microstructures, and cosmic visual data, and for translating them into a visual form. Within this logic, painting operates not as representation but as a mode of mapping, where infrastructural, planetary, and perceptual orders become co-visible across different scales and temporalities.

Tan Mu holds a BFA in Expanded Media from Alfred University, New York (2015), and graduated from the High School of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing (2011). Her work has been exhibited internationally, with solo exhibitions at Peres Projects (Berlin and Milan, 2022). She has participated in group shows at Arario Gallery, Shanghai, CN (2025); Penske Projects, New York; Winter Street Gallery, Martha’s Vineyard (2024); YveYANG, New York (2023). Her work has been featured and critically reviewed internationally, engaging themes of technology, memory, and visual abstraction across platforms such as Artnet News, Mousse Magazine, and Numéro Berlin. Her paintings are part of private and institutional collections internationally, including the A.R.M. Holding Art Collection (United Arab Emirates), the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection (Spain), and the Institute for Electronic Arts (United States).

Programs

Inspired by the spatio-temporal dimensions of Tan Mu’s Signal series, the music performance “Everything on the Line” imaginatively reads the paintings as graphic notation. Dots of urban hubs and lines of submarine cables resemble celestial bodies and constellations to conjoin the ocean and the sky. The canvases may evoke the ancient Greek geometric harmony, the Chinese cosmology embodied in Qin, or for a modern audience, the chance composition of John Cage. The authorship of these scores, though, lies as much with the painter and the musicians as with a dynamic world deeply shaped by submarine cables and other forms of technological infrastructure. The lines on the canvas are transformed into musical phrasings that transcend the physical distance between the artwork and the viewer.

The performance also attempts to create a multisensory experience full of nuances between the abstract and the mimetic, the durational and the two-dimensional. If one finds comfort of serenity and perpetuity in Tan Mu’s paintings, the performance gives a picture of what lurks beneath. The tangible lines on the string instruments turn into abstract sounds and vibrations. Each sound created on a single string resembles the fragility inherent in every connection in our human and natural world - everything on the line.

Sophie Steiner and Chatori Shimizu

2 September

Catalogue

Exhibition catalogue for Tan Mu: Signal, featuring essays by Nick Koenigsknecht, Li Yizhuo, and Sophie Steiner.

Limited editions are available, each with a unique drawing by Tan Mu.

Read online.

Media

Yiren Shen, “Tan Mu’s Interwoven World: Between Submarine Cable and Ocean Waves,” 10 Magazine, 26 August 2025.

Franka Magon, “In Conversation with Artist Tan Mu,” Numéro Berlin, September 2025.